Specialists—athletes who are good at one particular thing—are not unique to the sport of football, but the gridiron takes specialization to an extreme. Baseball, for instance, has its LOOGYs (left-handed one-out guys) who exist to enter the game, retire one left-handed batter, and hit the showers. And a basketball team might have players who are on the roster for their defensive prowess, or for perimeter shooting (none of whom are described using a term for a disgusting subgenre of spit). But in all these cases, the specialists are still going through the typical motions of the game—they are specialists because their skill set is proscribed, not unusual.

The eponymous members of football’s special teams, however, are idiosyncrasy made flesh. They perform highly specific, downright weird jobs that the convoluted evolution of the game has made necessary. The kicker’s most prominent assignment, for example, is to launch a ball between two big sticks with his foot. Nobody else on the field does anything that resembles this. The holder’s job on a field-goal attempt is to catch the ball after it is snapped and place it down, just so, to facilitate the kicker’s accuracy. Again, the skill of delicately positioning a football on the ground is fairly useless outside the limited context of a field goal, or perhaps a garden party.

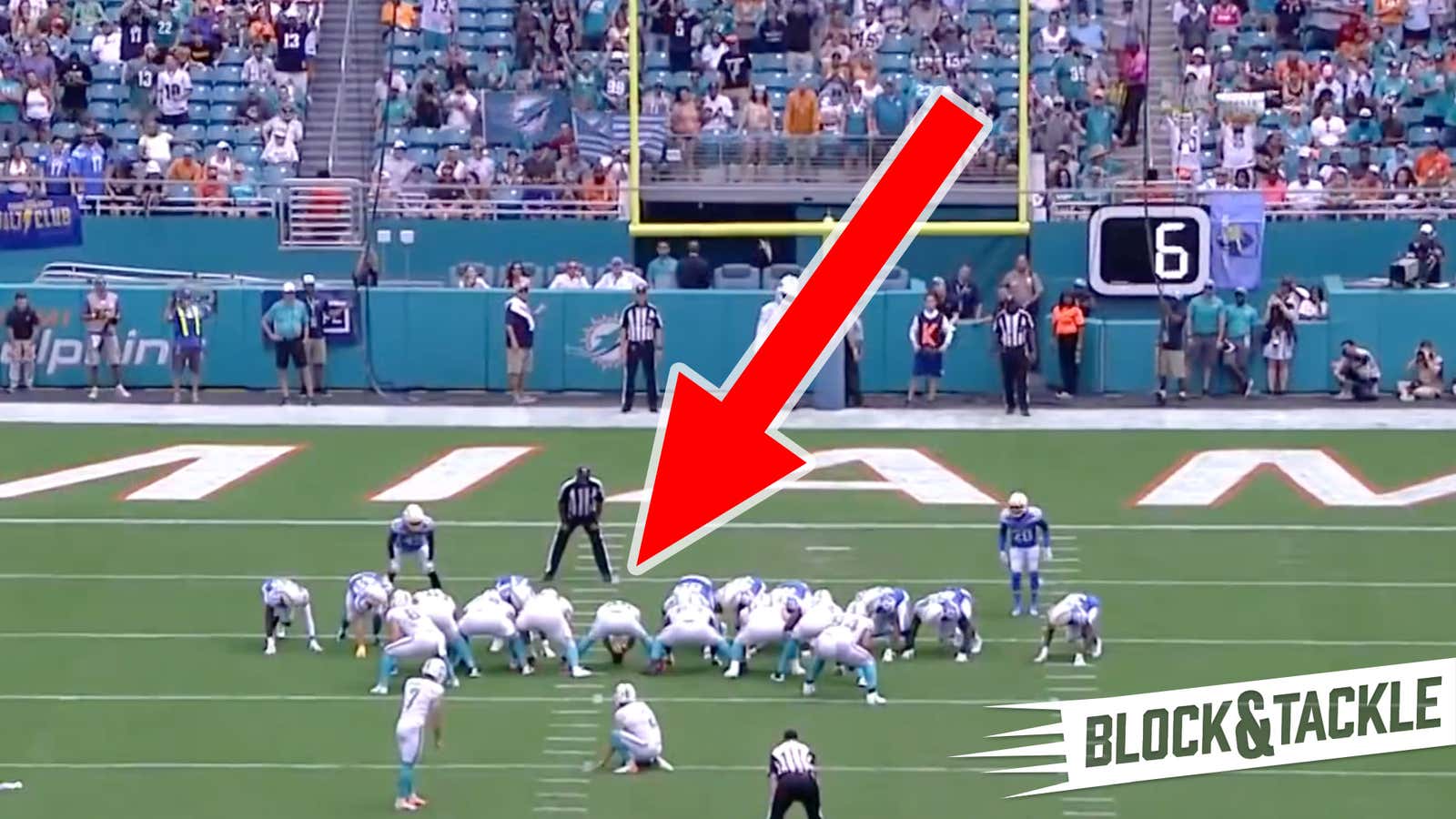

Then there is the long snapper, who participates only in field goals and punts. His lot in life is to bend down, look upside-down through his legs, and fire the ball a long distance (eight yards on a field goal attempt, about 15 yards on a punt) as fast as possible. By mastering a feat of bar-bet athleticism, a trick that seems like it was invented by some bored frat boys with a TikTok account, a highly trained between-the-legs ball-chucker can sustain an enduring career in the NFL. Long snapper John Denney, for instance, long snapped 14 years of long snaps for the Miami Dolphins before the team released him in September.

Denney’s successor on the Miami squad is Taybor Pepper, whom I recently noticed on Twitter, as the social media activities of NFL special-teamers have been a preoccupation of Block & Tackle for years. Pepper was alarmed, in capital letters, that EA had improperly banned his account from Apex Legends, a popular battle-royale shooter.

Both as a longtime game critic and as a player, I sympathized with the experience of being screwed by EA. Sensing a kindred spirit, I reached out to Pepper to see if he could illuminate football’s most underappreciated position for Block & Tackle readers, and he was happy to oblige. Here is our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Block & Tackle: First things first. Is your Apex account unbanned?

Taybor Pepper: I have not received the unban yet, no. I’m waiting, and I’ve talked to EA support, and they said there’s nothing they can do until the ticket gets looked at. I’m very impatiently waiting.

B&T: You can’t play the NFL card with them? They don’t care?

TP: I was hoping tweeting at them would do something, but apparently not.

B&T: I’m astonished by the bad customer service—although it is EA, after all. What makes Apex your battle royale of choice?

TP: I tried Fortnite, and I don’t like building, which—people who play Fortnite, that means I’m bad to them. [Laughs.] I like the movement style of Apex, [although] they kind of Nerfed the slide-jumping in season three, which I’m not sure if I’d be too happy about. I thought that was one of the things that made it unique. I also like that there’s no fall damage, because I can be kind of clumsy sometimes. [Laughs.]

B&T: Let me pivot to football. What do you wish people understood about the long snapper position that they generally don’t?

TP: It’s along the same lines as people’s awareness, or lack of awareness, about kickers. You know, we never go out there to miss or mess up. We understand that we have one job. We understand that. If you guys knew how many reps we get in our entire life—sometimes, if something doesn’t go right, we’re just as shocked as anybody else. We’ve spent our entire life dedicating ourselves to this, really, one motion—with snapping, it’s a little bit different in the NFL since you have to actually block after the [snap], so that does add another element of football to the long snapping position rather than just punting or kicking. But they’re all equally hard because—if your finger is one centimeter off on the ball from where it normally is, that could equal a foot or a yard by the end of the snap, by the time it gets to the punter.

Just know that we definitely know what our job is. That never gets mixed up in our brains. We take a lot of pride in it. We’re the most critical people of ourselves.

B&T: How do you deal with the fact that as soon as you snap the ball, a very large man is going to hit you as hard as he can?

TP: It’s definitely one huge jump from being a college long snapper to an NFL long snapper. Nowadays, a lot of colleges are running this spread-out formation where the long snapper really doesn’t have any blocking responsibilities. I made a name for myself while I was at Michigan State because I was able to snap and run down the field well—while I was in college. But when you get to the NFL, it’s a completely different game. Your only responsibility after the snap is to block. Until recent times, teams would never really care if they could get a long snapper into the coverage. Now they’re starting to [care], a little bit.

But knowing where the football is when your team possesses it, what part of the field you’re on, can clue you in to [whether] the return team is going to rush the punt or if they’re more concerned with making sure they can get the return that they want. This is my second year on [an NFL] team, but it’s my fourth year out of college. I’m still learning and surprised by so many things when it comes to different [defensive] fronts, and how you can read the way people are lined up. It kind of gives away what their intentions are.

B&T: How did you get into long snapping in the first place?

TP: My dad played college football at Illinois in ’89 and ’90, and he was in training camp with the Philadelphia Eagles after college. It’s a common thing you hear: When there’s young guys trying to make a team, you’re going to try everything you can do to stick. So he picked up the basics of long snapping. When I was in sixth grade, basically all he taught me is, “Put two hands on the ball.” That’s really it.

But honestly, that alone is what started it all. In eighth grade—the first year of school ball when I lived in Oklahoma—the coach shouted in the middle of practice, “If you want to try to be the long snapper, come over to this side of the field!” There were probably like 10 kids who walked over there. He said, “Just start snapping. We’ll let you know what we think.” Everybody would kind of shotgun snap the ball 12 yards—eighth grade, you’re not going to do the full 15. All these kids were one-hand snapping it. I was the only one with two hands on the ball. And the coach is walking down the line, he’s pointing at the kids, he goes, “You’re fired. You’re fired. You’re fired. Pepper, you’re hired.” Honestly, from then on out, I was like, “I’m a long snapper now!”

With my dad being a college football player, my whole life—it wasn’t pressure from my parents at all. I will applaud my parents every day of the week. There was never pressure, like, “You have to play college football. You have to play sports.” Which I really appreciate. But in the back of my mind, I was like, “Oh, I’m going to be a college football player.” There was no doubt. I get to 10th grade. I’m the third-string wide receiver. I’m the fourth-string defensive end. [I’m thinking,] “How the hell am I going to play in college, again? How is this going to work?” So 10th grade is when I started taking it seriously, going to [long snapping] camps and saying, “Hey, I could do this in college.”

B&T: So that was your route to college. But then when it comes to the pros, is it harder for young specialists to break into the league than it is for other positions?

TP: Yes and no. It’s hard to unseat some of these veterans who have been in the league five, 10 years, but it’s a double-edged sword. Because there’s a lot of turnaround, obviously, for wide receivers, O-linemen, stuff like that, but there’s a huge amount of wide receivers coming in every year. Huge amount of O-line. With specialists, it’s one spot on every team, but there’s a lot less kids coming out who are NFL-level punters, kickers, long snappers. It’s a give-and-take. Yeah, it’s harder, but for other reasons, it’s easier—because the longevity of, once you’re in, you can really be in for a long time.

I can’t really speak for punters and kickers, but every year, there’s usually two or three guys in each class who have a chance to develop as an NFL long snapper. And then once that happens, it’s going to be, who are the guys who continue to try? With me, I always felt I had that shot, but it took me two years to get my first shot, with the Packers. But really, four years to start the season with a team. That was huge for me. There were plenty of opportunities to give it up. Hang up my cleats and go do an internship, do a full-time job. The biggest key for guys who have the ability is to keep doing it. There’s a couple other guys I know personally that—they just wanted to get on with their lives. They didn’t have time to wait around. I can understand that.

B&T: What are the elements of good long snapping form?

TP: Each guy, it’s kind of like a fingerprint, honestly. Each guy has a little bit of their own style. When you’re learning, I would say it’s easier to tell kids, “Here’s a form you can stick to.” When it comes to a designed form, if kids are having a certain problem, and you know the form well enough that you’re teaching, it’s very easy to make changes to their form to fix the issues that they’re seeing. But you get so comfortable, as you develop and get older, you find things that work for you. You base it off whatever original form you learned, or if you just taught yourself. In the NFL, each person has their unique style.

B&T: When you got to Miami, you said you wanted to be “famous for not being known at all.” Can you elaborate on that?

TP: That’s generally the mind-set of all long snappers. The joke is, the only time fans know your name is when you mess up. It’s just an afterthought. Nobody thinks about the long snapper. Nobody thinks about the long snap on a punt. But it has more effect than a lot of people know. If you watch, week by week, all of the shanks that are kicked by punters, I would say easily half of them, the snap probably wasn’t in the best place for the punter. Our job is all about making the punter’s job easier.

Then on field goals, our job is to make the holder’s job easier, and the holder’s job is to make the kicker’s life easier. It’s just a minimization of mistakes. Because if I snap a ball to the holder and I mess up the laces, then it’s the holder’s job to erase my mistake. And if, for whatever reason, the holder doesn’t put it in the right spot, it’s on the kicker to minimize the holder’s mistake. It’s selfless.

B&T: You said you don’t want to mess up the laces. So you’re not just thinking about distance and positional accuracy. You also have to put the right amount of spin on the ball?

TP: Yeah, on field goals. [On punts], 15 yards is so long; I’m sure there are people who say they can control the laces on punts, but nobody really cares about that. But for field goals, it’s absolutely imperative that you’re able to snap the laces to the correct position every single time. Depending on how you hold the ball, it’s like two and a half rotations to the holder’s hands.

B&T: How many snaps a week are you doing in practice?

TP: When I was trying to learn how to do the laces? A ton, and then more on top of that. You have to get a feel for it, and then once you get a feel for it, you just drill that in. Now it’s one of those things I don’t have to think about that much. Now it’s more about position, where I’m snapping it. Some holders and coaches want the ball snapped right on top of where the spot is going be, at about the holder’s knee. Some holders want it more towards their chest so they can catch it cleanly. That differs a little bit. But yeah, learning how to do it was really hard.

I would say, reps per week—field goals, I have them pretty solidly down pat, so I would say 20, 25 a day on field goals. And then I usually like to get six to eight on film. I tend to get warm and then get a couple on film just for myself. I developed a rudimentary charting system. I grade each snap on a three-point system. I could do it on a more sophisticated level, but it’s more of a ritual at this point. I’ve talked with our sports psychologist about it. He definitely agreed that, as far as a ritual, it’s a good idea to keep watching the film and charting it the way I did this summer, when I was with the Giants.

B&T: I’m struck by the fact that different holders may like the ball at different positions. You also mentioned how each snapper has his own personal form. It sounds like part of your job is, when the units come together—the field goal units, the punt units—you guys have to figure out how you’re going to mesh with each other. Is that fair to say?

TP: Oh, totally. And that can make or break a lot of guys. Whenever you work as a team, no matter who it is, there are different personalities that have to come together. Sometimes it seems like it just doesn’t work. But when you get to the NFL, there’s a certain level of having to put that type of stuff aside. Then there’s [kicking] corps like the guys in Baltimore, who have been together for five-plus years, and they just mesh so well, and you’re like, how much does their relationship to each other affect [Baltimore kicker] Justin Tucker—in his accuracy, in his trust in them?

In college, and then in the pros, when it comes to camps, being with other specialists, you can totally tell when a kicker doesn’t trust the snap or the hold. You can just see it once you’ve been around it enough. So yeah, feeling each other out, and the camaraderie—if, for whatever reason, my snap isn’t good, my holder is going to know, “I trust you. That next one’s going to be perfect.” Then that next one, I don’t have to be jumpy and risk me messing up the hold. It’s a lot of trust.

Preview: San Francisco 49ers vs. Los Angeles Rams

Outspoken San Francisco 49ers cornerback Richard Sherman ignited the NFL Contretemps Of The Week after the 49ers’ Monday night 31-3 waxing of the Cleveland Browns. Having noticed that his personal brand has been underexposed (by his standards) so far this season, Sherman complained to NFL.com columnist Michael Silver that Browns quarterback Baker Mayfield failed to show proper respect during pregame rituals. According to Sherman, Mayfield neglected to shake his hand when the respective team captains met at midfield for the coin toss. “It’s ridiculous,” Sherman fumed on a night when his team had prevailed by a four-touchdown margin. “We’re all trying to get psyched up, but shaking hands with your opponent—that’s NFL etiquette.”

One of the best cornerbacks in league history, Sherman’s formidable on-field instincts are paralleled by a talent for extracting attention from the NFL’s media ecosystem. He knows where the pressure points lie, and “etiquette” is one of them. The league is populated by players who have grown up hearing their achievements hailed with blood-curdling screams from great masses of people. In this environment, they never developed a tolerance for even the mildest disrespect, so their egos are overinflated and prone to puncture. Accordingly, the hurt-feelings tale is a staple of NFL coverage. By now, the football press knows how to fan the flames of even the most minor upset. Sherman understands this.

On a more esoteric level, Sherman would also have understood the well-worn narrative arc for Cleveland Browns quarterbacks in particular. The Browns acquire new passers the same way a suburban household acquires new boxes of Honey Nut Cheerios, and as such, NFL commentators have developed a muscle memory for the progression of a new quarterback “era” in Cleveland.

First, pundits spend the offseason hailing the turnaround season that the new football-throw-person is sure to enjoy next year, raising expectations unfairly high. Then, once the season commences and the Browns fail to defeat all opponents by 70-point margins, the QB is recast as a defective specimen—bad body language, not too bright, appears in very few deodorant commercials—his failings simultaneously the cause and effect of Cleveland’s inexorable struggle.

It was the DeShone Kizer arc, and more emphatically before that, the Johnny Manziel arc. And there have been others. The modern Cleveland quarterback position never stops retelling the story of unreasonable hopes predictably thwarted.

After last year’s debut season in which he threw a rookie-record 27 touchdowns and led the Browns to an almost-not-losing-but-still-losing finish of 7-8-1, Mayfield became the latest QB to be anointed god’s gift to northern Ohio. Now the Browns are 2-3, so it’s time for Mayfield to have an “attitude” problem. Richard Sherman could smell the Honey Nut Cheerios growing stale, and he capitalized. He knows how to play the game outside the game, too.

The one hitch in Sherman’s “Baker Mayfield didn’t shake my hand” narrative was that Baker Mayfield did indeed shake his hand, and the handshake was captured on video from a variety of angles, given that it took place at an NFL game, where video cameras love to hang out. But this point of fact is a side note to the story. Its main effect was to offer Sherman another round of headlines on Wednesday, as he promised to apologize to Mayfield while arguing that the Cleveland passer still disrespected him in other, subtler ways. For instance, did you know that the pregame handshake, that exquisite dance of manners, even has unwritten rules about posture? “I took it as disrespect because the way he was standing back, like he wasn’t walking up and approaching like everybody else,” Sherman said.

Brilliantly playing every angle, Sherman also projected bemusement over the flurry of coverage he had knowingly and expertly orchestrated. “I thought the football game is what they watched for, but I guess it’s the soap opera,” said a man who ranks among the soap opera’s shrewdest performers.

In case it is unclear, I think Richard Sherman is hilarious and great.

This week, Sherman’s undefeated 49ers face the Los Angeles Rams. None of the Rams players took umbrage at a nonexistent coin-toss faux pas this week—they’ve just been practicing or whatever—so nobody cares about them. But returning to the topic of Richard Sherman, he has infused the game with an exciting storyline to watch. What other breaches of pigskin protocol might the Rams commit that will set Sherman’s cheekbones newly aflame with dudgeon? A partial list of possibilities:

- Left tackle Andrew Whitworth fails to curtsy before attempting a two-point conversion.

- Head coach Sean McVay throws the challenge flag on the field without including a self-addressed stamped envelope.

- After reeling off a big gain, running back Malcolm Brown performs the “feed me” gesture, but he pantomimes a dessert fork instead of a dinner fork.

- The Rams don’t say “gesundheit” when Sherman sneezes.

Keep your copy of Emily Post’s Guide To Meathead Etiquette close at hand during this game.

B&T mailbag: Quarterback revenge statistics and “burger” as suffix

Readers write in this week to discuss two topics close to my heart: rare football occurrences that nobody should care about, and the verbal clichés of the NFL media-plex.

First, perspicacious and good-smelling reader Sean McGowan touts a novel statistic of his own creation. Sean’s favorite play in football is an interception return, which is a fine choice. I, too, appreciate that first instant after an interception, when the 11 men on the squad formerly known as “the offense” say a collective “Oh, phooey” and resign themselves to chasing the upstart who plucked their leather oval from the air (without even asking first). Rarely in life does the situation arise where, in the middle of doing something, we are instantly expected to do the opposite thing. When you are playing the piano, no one asks you to do the opposite of that (filling a microwave oven with shaving cream).

But in football, an abrupt change of context happens all the time, and when it comes to an interception return, one of the most amusing role reversals is that once in a while, a quarterback makes a tackle. That is the subject of reader Sean’s new stat, Quarterback Revenge Rate (QRR). He writes:

I love interception returns, and I love even more when a quarterback atones for his mistake by tackling his interceptor. I wondered which quarterback was best at doing this, so I developed a statistic that I call the Quarterback Revenge Rate (QRR). Calculated by dividing a passer’s recorded tackles by his interceptions, QRR is a measure of how likely a quarterback is to tackle the defender who has just intercepted him.

Sean concedes that the statistic is imperfect, but it is as close to accurate as he can come using the Pro Football Reference play finder, a marvelous machine that has aided Block & Tackle’s own research on countless occasions.

Sean made a chart ranking the QRR of active players with data through the 2018 season. While the chart mysteriously has more bars than names, one thing is clear: Defenders should intercept Chicago Bears backup quarterback Chase Daniel at their own risk. If you’d like to know more, Sean has previously written an online internet blog post about QRR, an entertaining missive which claims to be a “9 min read,” but it only took me eight minutes. Aren’t you proud of me? Yes.

Next, shrewd and courteous reader Jacob Tipton writes Block & Tackle via electric mail to note that America’s favorite ground-beef sandwich is also fast becoming its favorite suffix:

Everybody is on the -burger train now. Any team that scores over 30 points has dropped a 30-burger. Tampa Bay was considered as having gone to LA and eaten a 50-burger. (However, there are no 10- or 20-burgers. Only 30 and above.)

The observation rings true. Jacob also provided a link to one representative example, in which an NFL person wearing a microphone on his face declares that the Houston Texans “dropped a 50-burger” in their 53-32 victory over the Atlanta Falcons. That remark comports with a pattern I’ve seen, in which the burger is typically “dropped”—sometimes “hung”—on the opponent. The implication of such imagery is that the losing team, one way or another, ends up with a burger attached to their person as a flame-broiled mark of shame. The only way out of this humiliating predicament, presumably, is to eat the burger. Therefore, a “burger” is a victory so massive that it is liable to cause the loser uncomfortable constipation the next day.

What is free-agent punter Marquette King up to this week?

This week, Block & Tackle’s favorite free-agent punter, Marquette King, is dancing with robots after hours outside a Tokyo karaoke bar. The apocalypse may or may not have occurred before the dance began. At press time, it was rumored that the Denver Broncos have signed the second robot from the left to their practice squad.

Since Marquette King is so busy hanging out with machine beings from the Far East who replicate his every move, an uninformed observer might conclude that King isn’t focused on making a return to pro football. To dissuade NFL decision-makers from that notion, King set aside time to remove his shirt and create a workout video, in which he rather handsomely performs one (1) front dumbbell raise and then one (1) bicep curl, all without scuffing the bright gold Batman logo on his cap. “You’re safe with me, sweat,” King seems to say. “I will never break you.”

Block & Tackle will keep you apprised of further Marquette King developments as they unfold.

Your Week 6 QuantumPicks

Block & Tackle is the exclusive home of the QuantumPick Apparatus, the only football prediction system that evaluates every possible permutation of a given NFL week to arrive at the true victor in each contest. Put simply, Block & Tackle picks are guaranteed to be correct. When a game’s outcome varies from this column’s prediction, the game is wrong.

In Week 5 NFL action, eight games corresponded with the QuantumPicks, and seven games were incorrect. Would that I could be heartened by this slim triumph of sense over disorder, but we must remain vigilant. The malevolent forces of unreality threaten to distort the fabric of our existence every Sunday whenever a football contest diverges from the one true universe—the existence that can be glimpsed only by the QuantumPick Apparatus and by the QuantumPick Apparatus’ cousin, Trevor Apparatus. (Overall season record: 46-32.)

Teams determined to be victorious by the QuantumPick Apparatus are indicated in SHOUTING LETTERS.

Thursday Night Football

New York Giants vs. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (Fox) (time-stamped pick)

Sunday Games—Early

Carolina Panthers vs. TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS (NFL Network, from London, 9:30 a.m. ET)

Cincinnati Bengals vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (CBS)

Houston Texans vs. KANSAS CITY CHIEFS (CBS)

NEW ORLEANS SAINTS vs. Jacksonville Jaguars (CBS)

SEATTLE SEAHAWKS vs. Cleveland Browns (Fox)

Washington vs. MIAMI DOLPHINS (Fox)

PHILADELPHIA EAGLES vs. Minnesota Vikings (Fox)

Sunday Games—Late

ATLANTA FALCONS vs. Arizona Cardinals (Fox)

SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS vs. Los Angeles Rams (Fox)

DALLAS COWBOYS vs. New York Jets (CBS)

Tennessee Titans vs. DENVER BRONCOS (CBS)

Sunday Night Football

Pittsburgh Steelers vs. LOS ANGELES CHARGERS (NBC)

Monday Night Football

Detroit Lions vs. GREEN BAY PACKERS (ESPN)

Teams on bye

The Buffalo Bills, Indianapolis Colts, Oakland Raiders, and Chicago Bears have decided not to play football this week. They will automatically forfeit, and their transgression will be reported to the commissioner’s office.

Talk backle to Block & Tackle

If you’d like to contact me with an item for Block & Tackle, or just to say hello, you can email me: my first name, at symbol, my full name, dot com. You can also reach me via Twitter. Thank you for reading, and for the funny and smart comments. Until next time, keep on long snappin’.