Note: The writer of this review watched Promising Young Woman on a digital screener from home. Before making the decision to see it—or any other film—in a movie theater, please consider the health risks involved. Here’s an interview on the matter with scientific experts.

Promising Young Woman has the bright, alluring sheen of a pop confection. The paint-swatch spectrums of pink and blue—powder to electric neon, baby to deep navy—that dominate its color palette are both soothing to the eyes and in step with Instagram trends. Its soundtrack, packed with 21st-century bubblegum pop, imparts a similar sweetness. The title character wears fuzzy floral sweaters and sucks on red licorice, and every shade of girly, from kawaii to rococo, splashes across the screen at some point. Then there’s the cast, which is full of reassuringly familiar faces, from Adam Brody and Christopher Mintz-Plasse to Laverne Cox and Alison Brie. But the hard-candy shell that coats the film conceals a razor blade, ready to cleave the tongues of those entitled enough to chomp down without letting it melt in their mouths first.

In fact, the primary target of this feature debut from one-time Killing Eve showrunner Emerald Fennell is entitlement—specifically, the idea that a man’s potential is worth more than a woman’s well-being. Fennell’s script for Promising Young Woman quakes with a fury toward the Brock Turners of the world; it tracks the long-term consequences of a campus sexual assault that was dismissed and quickly forgotten by both the victim’s friends and university officials. But Cassandra (Carey Mulligan) remembers. Radicalized by the event, she drops out of medical school and reorganizes her life around getting revenge on all those who allowed this frat-boy rapist to walk free—as well as any man who thinks that “blackout drunk” is synonymous with “sexually available.”

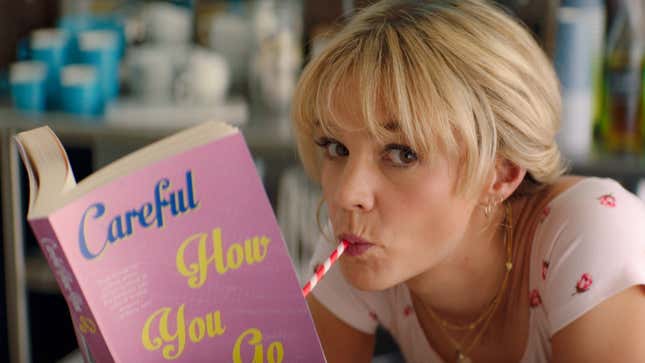

Much like a horror movie, Promising Young Woman opens with a kill scene. (Or does it? The film remains coy on this point for a moment.) A clique of men in business suits gather around a loud, pulsating bar, bitching about how they can’t even go to strip clubs on the company dime anymore. The camera pans over to Cassandra draped over a red vinyl booth in Christlike repose, so wasted she doesn’t seem to notice that her skirt has risen up far enough to expose her underwear. Jerry (Brody), the gentleman of the group, offers to take her home, only to “change his mind” and bring her back to his apartment mid-ride share. He made his choice, and now he’ll pay for it—as Mulligan reveals when her expression changes from sloppy to stone-cold sober like the flip of a switch. She’s not a lost lamb but a hunter on the prowl, and Jerry here is about to learn his lesson about taking advantage of drunk women.

Although Promising Young Woman starts as a straightforward revenge tale, Fennell treats it more like a thought experiment than a thriller, exploring Cassandra’s vigilante campaign from different angles. This includes her relationship with her parents, who think she’s a fuck-up and probably a drug addict. There’s also the question of what happens when one of her targets shows genuine remorse for what he’s done. And what about when Cassandra meets a man she actually likes? (Promising Young Woman does not hedge or fence-sit; it’s a misandrist film, and proud of it.) Shifting tones keep the film interesting even when it meanders, and it’s clear that Fennell has thought through every detail, from the dialogue (one sleazy guy in a fedora complains that surge pricing is at 1.2, so they’re going to have to walk back to his place) to its intricate endgame. This attention to detail also means that the film stands up to multiple viewings, each provoking new questions.

Cassandra is not a righteous avenger. In fact, as the film wears on, she begins to look more like a supervillain. One of the film’s most provocative and under-explored elements is its interrogation of alcohol and the role it plays in consent; Cassandra hates men who victimize drunk women, but isn’t above drugging a drink if it’ll assist in her mission. The most uncomfortable manifestation of this element comes when Cassandra meets up to have drinks with an old school friend, Madison (Brie). Cassandra has an ulterior motive, of course, and plies Madison with wine and champagne while staying sober herself. Once she’s gotten what she wants, Cassandra leaves Madison drunk in a hotel bar, instructing a man she hired to do… something with her estranged pal.

Promising Young Woman fancies itself edgy, and relishes complicating the catharsis of something like the scene where Cassandra smashes some douchebag’s windshield with a tire iron after he yells at her on the road. But while the craft of the film is top-notch, and the writing razor-sharp, its nihilistic point of view isn’t as unprecedented as Fennell seems to think it is. This film is enamored with its own cleverness—and it is clever. But there have been a handful of indies this decade that covered similar ground, and while naming some of them would give away too much, Natalia Leite’s M.F.A. (2017) is the obvious forerunner to Promising Young Woman’s core conceit.

That film played a handful of genre film festivals, and had a minuscule theatrical release, thanks in part to an upsettingly explicit scene of sexual assault that made it a rough sit for general audiences. Maybe the world just wasn’t ready then; by contrast, the reception to Promising Young Woman at this year’s Sundance Film Festival was mostly rapturous. The surface accessibility of this film is presumably part of the point, forcing conversations that have been happening on the edges of the film world into the mainstream. And the simple fact that two films released three years apart could have the same white-hot rage at their core says a lot about the intractability of rape culture. Promising Young Woman’s anger may not be unprecedented but it is justified.